Iron ore, as the core raw material for smelting metallic iron, is a fundamental mineral resource supporting global industries such as construction, transportation, and machinery. Its industrial supply chain is directly linked to the stable operation of the steel industry. Iron is the most consumed metallic element globally, accounting for 95% of total annual metal consumption, far exceeding other industrial metals such as aluminum and copper. As the primary natural carrier of iron, the quality and supply stability of iron ore directly determine the production capacity and efficiency of the steel industry. Industry statistics show that 98% of global iron ore is used for steel smelting, while the remaining 2% is precisely matched to the needs of specialized fields such as pigments, catalysts, and medical tracers. The development and utilization of iron ore are highly intertwined with the development of heavy machinery technology. From large excavators in open-pit mining to crushing and sintering equipment in the processing stage, the performance of heavy machinery directly determines mining efficiency, processing precision, and overall cost.This article comprehensively integrates the core information of the entire iron ore chain, from geological occurrence to market application, and focuses on analyzing the application logic of heavy machinery in each link, providing practical reference for industry production and machinery selection.

Basic properties of Iron and Iron ores

Geological distribution characteristics

Iron ore is widely found in three major rock types: igneous rocks, metamorphic rocks, and sedimentary rocks. Approximately 60% of industrial iron ore deposits fall into the sedimentary rock category, a typical example being the hematite deposits in the Hamersley Basin of Australia, whose formation is closely related to the Proterozoic shallow marine sedimentary environment. However, some iron ore deposits have had their original geological origins obscured by long-term weathering and groundwater erosion, making precise determination of their origin difficult. For instance, some limonite deposits in North China were formed by the weathering and alteration of hematite. Major global iron ore deposits are concentrated in specific geological zones, forming distinct metallogenic concentration areas: the Hamersley Basin in Australia has proven reserves exceeding 50 billion tons, the Carajás field in Brazil has single-mine reserves of 7.27 billion tons, the Lake Superior region in the United States has cumulative proven resources exceeding 30 billion tons, and North China has formed a large iron ore concentration area centered on Anshan-Benxi. These areas, with deposits generally exceeding 55% grade or having reserves exceeding 1 billion tons, have become core regions for global industrial mining. Iron Knight and Iron Duchess mines in South Australia are currently the main operators, and local leading companies have integrated regional assets to form a complete industrial chain from mining to processing.

Influence of material composition and impurities

The core component of iron ore is iron oxide. The main iron-bearing minerals include hematite, magnetite, limonite, and siderite. Due to differences in crystal structure, the theoretical iron content and chemical stability of different minerals vary significantly. In addition to iron-bearing minerals, iron ore commonly contains commercially worthless gangue components such as quartz, feldspar, and calcite. Among these, silicon (SiO₂) and phosphorus compounds (P₂O₅) are the most prominent harmful impurities to steel production: silicon reacts with lime during smelting to form high-melting-point calcium silicate slag, increasing energy consumption and slag treatment costs, while also reducing the weldability of steel; phosphorus forms brittle phosphides in steel, causing "cold brittleness" fracture at low temperatures. Furthermore, some deposits also contain impurities such as sulfur and arsenic, which need to be removed in advance through processes such as flotation and roasting, further increasing the complexity of the production process.

| Main Iron-bearing Mineral | Chemical Formula | Theoretical Iron Content (%) | Appearance Characteristics | Suitability for Heavy Machinery |

| Hematite | Fe₂O₃ | 69.9 | Red, light gray or black, red streak, metallic luster | Medium hardness, suitable for conventional crushing equipment, no special wear-resistant parts required |

| Magnetite | Fe₃O₄ | 72.4 | Black or dark gray, black streak, strong magnetism and metallic luster | High density (4.9–5.2 g/cm³), requires enhanced wear resistance of crusher hammers, magnetic separation requires dedicated equipment |

| Limonite | 2Fe₂O₃·3H₂O | 59.8 | Yellow-brown or black-gray, earthy luster, water content 15%–25% | Easy to stick and clog, crushing equipment must be equipped with scraper-type anti-blocking devices, subsequent briquetting equipment required |

| Siderite | FeCO₃ | 48.2 | Gray or yellowish-brown, vitreous luster, easily weathered to limonite | High brittleness, high crushing efficiency, requires drying equipment pretreatment before calcination |

Commercial Taste Standards

The commercial grade of iron ore is primarily determined by its iron content. This standard stems from a quantitative balance between smelting costs and profits: for deposits with an iron content below 30%, the combined energy consumption for gangue processing, transportation costs, and smelting losses exceed the economic value of iron, thus rendering them uncommercially viable for mining. In industrial production, influenced by the genesis and subsequent alteration of deposits, the iron content of common iron ores is concentrated between 50% and 60%. For example, the average iron content of hematite deposits in Bihar, India, is 56%-58%, and the average iron content of magnetite deposits in the Ural Mountains of Russia is 54%-57%. Some high-quality deposits, due to intense subsequent enrichment, can reach grades exceeding 66%. For instance, the Tom Price mine in the Hammersley Basin of Australia maintains a stable hematite grade of 65%-68%, while the highest grade of massive hematite in the Carajás mine in Brazil reaches 69%. The industry defines hematite or magnetite with an iron content of over 60% as direct-load ore (DSO). This type of ore only requires simple crushing and screening before it can be directly fed into the blast furnace for smelting, without the need for complex purification and pretreatment. It is the mainstream type of iron ore trade and industrial mining in the world today.

Main iron and iron ore types and core characteristics

High-grade iron and iron ore

High-grade iron ore mainly includes two types: hematite and magnetite. Due to their high iron content and low impurities, these two types together account for more than 90% of the world's industrial iron ore consumption and are the core resources supporting global steel production capacity.

- Hematite is the most widely used type of iron ore. Its deposits are mostly of shallow marine sedimentary origin, forming industrial ore bodies through subsequent regional metamorphism or fluid enrichment. Core producing areas include the Hamersley Basin in Australia (proven reserves of 50 billion tons), the Carajás mine in Brazil (reserves of 7.27 billion tons), and the Bihar-Jharkhand mining area in India (reserves of 12 billion tons). Hematite crystals belong to the trigonal crystal system, and under an electron microscope, typical platy or columnar crystal structures are visible. Some deposits, such as the Mount Whaleback mine in Australia, have formed massive hematite ore bodies with a thickness of 50-80 meters through fluid enrichment by hyperthermic groundwater, with a stable grade of over 65%, making it one of the world's highest-quality steelmaking raw materials.

- Magnetite is the type of iron ore with the highest theoretical iron content. Its strong magnetic properties give it a unique advantage in separation – through a high-intensity magnetic separator with a magnetic field strength of 1000-1500 Oersted, it can be quickly separated from gangue, and after purification, iron concentrate with an iron content of over 70% can be obtained, with some high-quality deposits even reaching a concentrate grade of 72%. Magnetite deposits are mainly distributed in the Pilbara region of Australia, Mesabi Ridge in Minnesota, USA, and Labrador region in eastern Canada. Among them, the magnetite deposits in the Pilbara region of Australia are often associated with ilmenite (TiO₂ content 5%-8%) and vanadium iron ore (V₂O₅ content 0.1%-0.3%). The combined output value of iron ore and liquefied natural gas industries in this region exceeds 7 billion Australian dollars, accounting for more than 70% of the mineral energy output value of Western Australia. Through the combined process of magnetic separation and flotation, iron, titanium, and vanadium can be comprehensively recovered, significantly improving the economic value of the deposits. The magnetite deposits in Minnesota, USA, are layered with ore bodies 100-150 meters thick and shallowly buried, making them suitable for large-scale surface mining. The magnetite concentrate produced there has extremely low impurity content, making it a dedicated raw material for producing high-strength automotive steel sheets.

low-grade iron ore Fe ore

Low-grade iron ore, including limonite, siderite, and taconite, generally has an iron content below 60% and requires targeted purification to meet smelting requirements.

- Limonite is not a single mineral, but rather a hydrated iron oxide mixture with goethite as its core, containing lepidocrocite and hygroscopic ferruginous iron. Its water content is typically between 15% and 25%, and it mainly forms in paleochannel sedimentary environments or the weathering zones of primary iron ore deposits, such as the paleochannel sedimentary limonite deposits in the Rhine River basin of Germany. Due to its high water content, directly feeding limonite into the furnace would lead to a surge in smelting energy consumption. Therefore, it requires briquetting before smelting—limonite powder is mixed with a binder, pressed into lumps under 10-15 MPa pressure, dried at 105°C to remove surface water, and then fed into the blast furnace. Historically, during periods of high-grade ore shortage, limonite was widely used as a low-grade ironmaking feedstock.

- Siderite is an iron carbonate mineral with the unique advantage of being free of harmful impurities such as sulfur and phosphorus, giving it a natural advantage in the production of ultra-low sulfur and phosphorus steel. However, its theoretical iron content is only 48.2%, and in actual deposits, due to the presence of carbonate gangue, the iron content is mostly between 35% and 45%, requiring calcination to increase the iron concentration. The calcination process is typically carried out in a rotary kiln at 800-900℃. Siderite decomposes into iron oxide, carbon dioxide, and water. After calcination, the iron content can be increased to 55%-60%, and the product has a porous structure with an increased specific surface area, making it easily reduced by reducing agents such as coke, suitable as a raw material for the direct reduced iron (DRI) process.

- The Taconite mine specifically refers to a low-grade mixed ore deposit located in the Lake Superior region of the United States. It is primarily composed of magnetite, hematite, and quartz gangue, with a stable iron content of 25%-30%. It requires a three-stage purification process—coarse crushing, fine grinding, and wet magnetic separation—to obtain a concentrate with an iron content exceeding 65%. The proven resources in this mining area exceed 20 billion tons, making it a crucial reserve resource for the US steel industry. Low-grade banded iron ore (BIF) resources are equally important. South Australia's Eyre Peninsula alone has proven BIF resources exceeding 2.5 billion tons, with an iron content of 20%-30%. Furthermore, the state has identified three other iron ore provinces: the Eyre Peninsula, the Mount Woods Inland-Eagle's Nest region, and the Nacala Arc Brema region, with a combined low-grade resource exceeding 10 billion tons.

Global Iron Ore Production and Sales Pattern

Resource reserves and production distribution

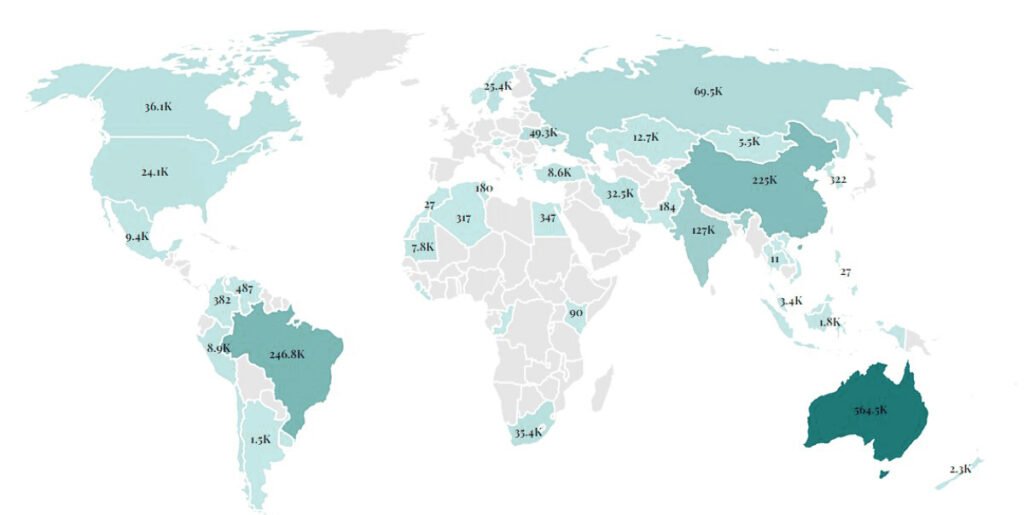

Global iron ore reserves are extremely abundant. According to a 2023 statistical report released by the International Commission on Minerals (ICMM), global crude ore reserves exceed 800 billion tons, of which iron content exceeds 230 billion tons. Based on the current global mining scale of 2.95 billion tons per year, the static guarantee life can reach over 70 years. Resource distribution exhibits significant characteristics of "large total volume, uneven grade, and regional concentration." Low-grade ore (30%-50% iron content) accounts for over 70%, mainly existing in banded iron formations (BIF), while current industrial production primarily relies on high-grade hematite and magnetite, which account for less than 30%.

- Globally, 50 countries engage in iron ore mining, but production is highly concentrated, with 96% of output concentrated in 15 countries. The top five producers are China (1.02 billion tons), Australia (880 million tons), Brazil (410 million tons), India (210 million tons), and Russia (150 million tons). Adding India, the United States, Canada, and Kazakhstan, these nine countries account for 80% of global production, forming a clear oligopoly.

- Australia is the world's largest iron ore producer, with an actual output of 880 million tons in 2023, accounting for 29.8% of global production. Its core production area is the Pilbara region of Western Australia, which is home to 16 large mines operated by several leading companies. These mines account for over 70% of Western Australia's total mineral energy output, with the Hamersley Basin alone having an annual production capacity of 600 million tons.

- Brazil is the world's second-largest iron ore producer, with an output of 410 million tons in 2023. Its core production area, the Carajás field, is the world's largest single iron ore deposit, with reserves of 7.27 billion tons and a stable grade of over 66%. It utilizes large-scale open-pit mining equipment, with an annual production capacity of 130 million tons.

- South Australia, a major iron ore producing region in Australia, has seen its Iron Knob mine, which began production in 1915, produce over 200 million tons of high-grade ore, making it Australia's first large-scale iron ore mine.

The global iron ore production landscape is dominated by "three Australians and one Brazilian": Vale of Brazil produced 319.6 million tons in 2021, Rio Tinto of Australia produced 276.6 million tons, BHP Billiton produced 245.4 million tons, and Fortescue Metals produced 84.7 million tons. The four companies produced a total of 926.3 million tons in 2021, accounting for more than 60% of the global total, and have a strong influence on global iron ore pricing.

Trade Flows and Consumption Characteristics

The global iron ore trade exhibits a highly concentrated pattern of both production and consumption. Brazil, Australia, Canada, and India are the four major exporting countries, with Australia and Brazil together accounting for 63% of global exports. Australia alone exported 896 million tons in 2022.

- Australia possesses significant logistical advantages in trade: its specialized iron ore ports in the Pilbara region, such as Port Hedland and Port Dampier, are equipped with dedicated 300,000-tonnage berths and automated loading systems, achieving a loading efficiency of 12,000 tons per hour. Exports to Qingdao Port in China are only 4,800 nautical miles away, with a transit time of approximately 12 days.

- In contrast, exports of Brazilian Carajás ore must pass through Victoria Port, a distance of 11,000 nautical miles from China, with a transit time of up to 45 days, resulting in logistics costs more than 30% higher than in Australia. Official Australian data shows that iron ore exports reached 896 million tons in the 2022-23 fiscal year (up 2.5% year-on-year), generating AUD 113 billion in revenue. Exports are projected to increase to 920 million tons in the 2023-24 fiscal year (up 2.7% year-on-year), but revenue is expected to fall to AUD 95 billion due to declining prices. In 2021-2022, Australia's iron ore export revenue to China reached AUD 108.9 billion, with China being its largest buyer, accounting for 62%-82% of its export demand. This close trade relationship directly impacts the coordinated development of the mining and steel industries in both countries.

China is the world's largest consumer of iron ore and also the world's largest producer of steel. In 2022, China's crude steel production reached 1.013 billion tons, accounting for 51.7% of global crude steel production, corresponding to iron ore consumption of 1.12 billion tons, accounting for over 50% of the global total, of which over 90% is imported. Japan, the EU, and the US are the world's second-largest consuming regions. In 2022, Japan consumed 120 million tons of iron ore, the EU 110 million tons, and the US 80 million tons. These regions, due to insufficient domestic iron ore resources, all have import dependence rates exceeding 90%. Japan mainly imports from Australia and Brazil, while the EU diversifies its sources, including India and South Africa. Global iron ore consumption maintained a high annual growth rate of 10% between 2010 and 2020, mainly driven by the demand for real estate and infrastructure construction during China's urbanization process. In 2022, affected by factors such as global inflation and China's real estate regulation, demand experienced a short-term decline. Global crude steel production fell from 85.5 million tons in 2021 to 82 million tons, and iron ore production fell from 268 million tons to 260 million tons. In 2023, with the stabilization of the global economy and the recovery of infrastructure investment in China, consumption gradually recovered to the 2021 level.

Fe Ores Mining and Processing Technology

Iron and Iron ore Mining methods and technology applications

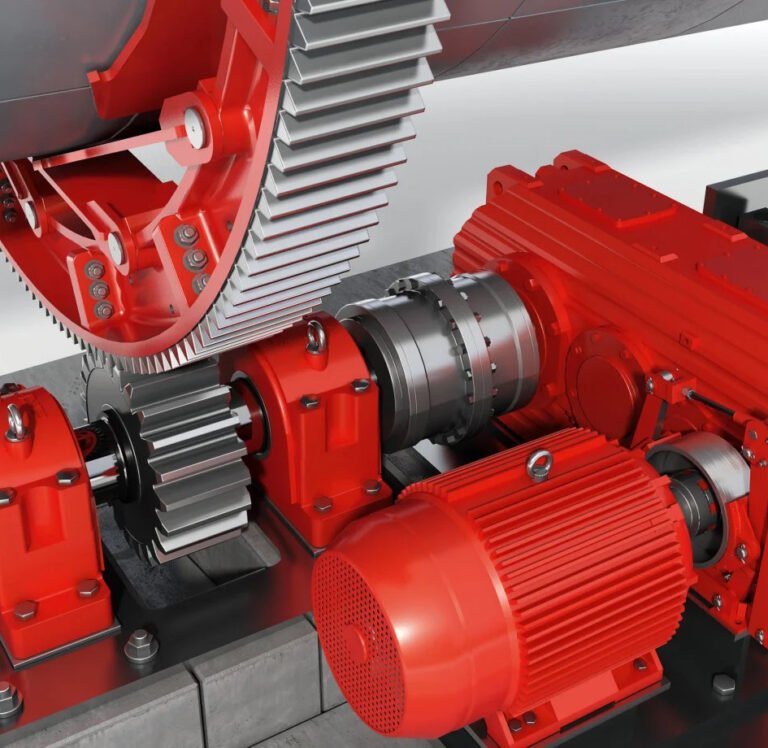

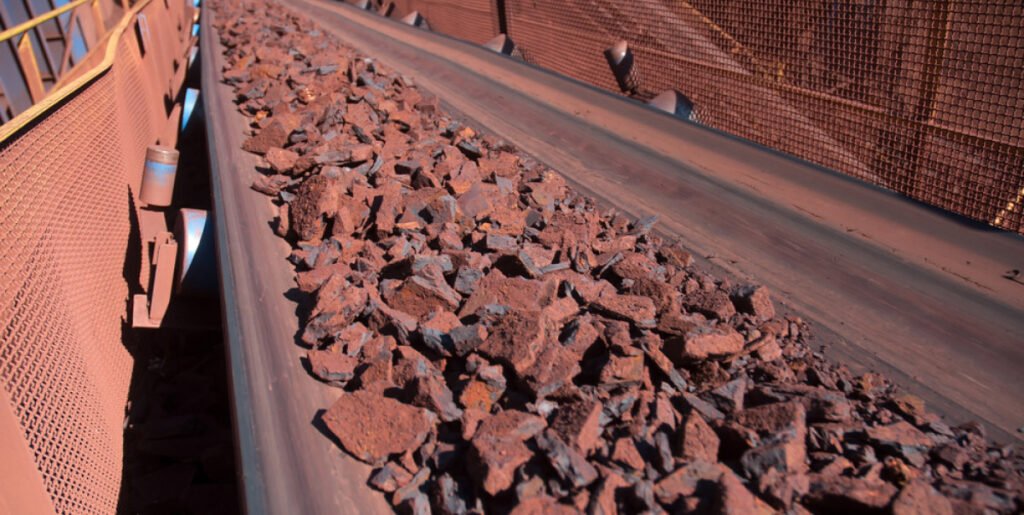

- Mining is primarily surface mining (open-pit mining), accounting for over 85% of global mining volume. This method, which involves stripping away the surface overburden and extracting ore layer by layer, offers advantages such as low cost, high efficiency at scale, and high safety. Core equipment for open-pit mining includes large excavators (bucket capacity exceeding 50 cubic meters), dump trucks (load capacity exceeding 300 tons), and tracked bulldozers. Some mining areas have achieved automated mining, using unmanned equipment and remote monitoring systems to improve efficiency and reduce labor costs.

- Underground mining accounts for only 15% of global mining volume and is mainly suitable for deep, high-grade deposits or areas with excessively thick surface overburden. Underground mining requires steps such as tunnel excavation, support system construction, ventilation, and drainage to ensure safety. Common methods include room-and-pillar methods, caving methods, and backfilling methods. The core technical challenges lie in controlling ground pressure, preventing roof collapse, and managing gas. In recent years, intelligent underground mining technologies have been gradually applied, using technologies such as the Internet of Things and big data to achieve real-time monitoring of the mining process and improve resource recovery rates.

Fe Ore Processing flow and core technologies

The core objective of Fe Ores processing is to transform raw ore into feedstock that meets the requirements of blast furnace smelting. The processing flow varies significantly depending on the grade of the mineral. The technical parameters and application scenarios of the main processing technologies are shown in the table below:

| Process | Applicable Raw Material | Key Equipment | Core Steps | Product Specification | Capacity Level |

| Crushing & Screening | High-grade DSO ore (Direct Shipping Ore) | Jaw crusher, cone crusher, vibrating screen | Primary crushing (≤300 mm) → Secondary & tertiary crushing (≤25 mm) → Screening & grading | Lump ore 7–25 mm, Fines <7 mm | 10,000–50,000 t/day per line |

| Grinding & Beneficiation | Low-grade ore (25%–30% Fe) | Ball mill, spiral classifier, magnetic separator, flotation cell | Crushing → VRM Grinding Mill (-200 mesh ≥80%) → Classification → Magnetic separation / Flotation → Dewatering | Iron concentrate TFe ≥65%, SiO₂ ≤4% | 500–2,000 t/day per ball mill |

| Sintering | Iron ore fines (<7 mm), return fines, fluxes | Traveling grate machine (sinter strand), ignition furnace, exhaust fan | Batching (fines + coke breeze + fluxes) → Mixing → Charging → Ignition → Sintering → Cooling → Crushing & screening | Sinter size 7–25 mm, Tumbler Index ≥60% | 10,000–25,000 t/day per sinter strand |

| Pelletizing | High-grade iron concentrate (TFe ≥65%) | Drum or disc pelletizer, chain grate – rotary kiln, annular cooler | Batching → Mixing & moistening → Green balling (8–12 mm → Drying → Preheating → Roasting (1250–1340 °C) → Cooling | Pellets diameter 10–15 mm, Compressive strength ≥2500 N/pellet | 1–5 million tons/year per line |

- The processing flow for high-grade minerals (DSO) is relatively simple. After crushing and screening, lump ore is directly fed into a blast furnace for smelting, while fine ore is sintered to form lumpy raw materials.

- Low-grade minerals require a complete processing flow: the raw ore is crushed to 0-12 mm and then ground in a ball mill. A spiral classifier controls the particle size, and unqualified powder is returned for regrinding.

- Benefitting technologies are selected based on mineral properties—for magnetite, a high-intensity magnetic separator (magnetic field strength 1000-1500 mT) is used to remove gangue such as quartz. For complex hematite, a combination of spiral sluice (gravity separation), magnetic separator, and flotation is used to improve the grade of iron concentrate.

- After dehydration by a disc filter and drying by a dryer, the iron concentrate is sintered or pelletized to form lumpy raw materials, avoiding the problems of poor permeability and low reduction efficiency caused by fine powder in the blast furnace.

Iron and Iron ore resource recycling and environmental protection

Tailings generated during processing (accounting for 30%-50% of the raw ore processed) can be recycled through multiple technologies:

- After crushing and grading, the tailings are made into high-quality concrete aggregates for use in road construction, building engineering, and other fields.

- Associated elements such as titanium, vanadium, and rare earth elements in some tailings are recovered through specialized mineral processing technologies (such as flotation and gravity separation), achieving comprehensive utilization of associated resources.

- After ecological restoration, tailings ponds can be transformed into farmland, forest land, or industrial land, reducing environmental impact.

Environmental protection measures during the processing mainly include:

- Dust control utilizes bag filters and electrostatic precipitators to achieve emission standards;

- Wastewater is recycled after sedimentation, filtration, and neutralization, with a reuse rate exceeding 95%;

- Sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides generated during the sintering process are treated by desulfurization and denitrification equipment to reduce air pollution;

- Some enterprises employ waste heat power generation technology to recover waste heat from sintering and pelletizing processes, achieving cascaded energy utilization.

Fe Ores Iron Ore Application Areas

Core application: Iron and steel smelting

98% of the relevant minerals are used in steel manufacturing. The raw ore is smelted in a blast furnace to produce pig iron (containing 4%-5% carbon), and then steel is made in a converter to remove impurities such as silicon, phosphorus, and sulfur and adjust the carbon content, or alloyed with elements such as tungsten, manganese, nickel, vanadium, and chromium to produce different types of steel products, forming a complete industrial chain of "minerals - pig iron - steel - end products".

Steel applications cover almost all industrial sectors:

- In the construction industry, rebar and wire rod are used in building construction and bridge construction, while H-beams and channel steel are used in steel structure workshops.

- In the transportation industry, steel accounts for 60%-70% of the weight of automobiles, including body panels and engine parts. Steel used in high-speed rail tracks must meet high strength and high wear resistance requirements, while steel used in shipbuilding must possess corrosion resistance and impact resistance.

- In the energy industry, steel used in oil and gas pipelines must withstand high-pressure and low-temperature environments, while steel used in wind turbine towers must possess high toughness and fatigue resistance.

- In the machinery manufacturing industry, core components of machine tools and construction machinery mostly use alloy structural steel.

The different industries' requirements for steel quality directly affect the demand structure of related minerals: high-end manufacturing industries (such as aerospace and precision machinery) require low-phosphorus, low-sulfur, and high-purity steel, corresponding to requirements of phosphorus content ≤0.03% and sulfur content ≤0.02% in the minerals; construction steel has relatively relaxed requirements for impurity content and can use steel smelted from medium- and low-grade minerals.

Fe Ores Secondary Applications: Specialized Fields

The remaining 2% of iron ore and iron compounds are precisely matched to the specialized needs of specific fields, forming a segmented application market.

- Iron powder applications are categorized by particle size into several grades: atomized iron powder (200-500 mesh) is used in the manufacture of permanent magnets and high-frequency magnetic cores; reduced iron powder (100-200 mesh) is used in powder metallurgy forming of automotive parts; and ultrafine iron powder (500-1000 mesh) is used as a chemical reaction catalyst.

- Radioactive iron (iron 59) is a specialized tracer in medical and metallurgical research. With a half-life of 45.1 days, it can be used to track the metabolic pathway of iron in human hemoglobin synthesis or to monitor element migration patterns in iron ore during smelting, either through injection or addition.

- Iron blue, as a high-performance pigment, possesses excellent lightfastness and tinting strength. It is added at 5%-10% in paints and printing inks, and at 1%-3% in cosmetics such as eyeshadow. It can also be used as an industrial coating for rust prevention in automotive chassis.

- Black iron oxide is classified into industrial grade (95% purity) and pharmaceutical grade (99% purity) based on purity. Industrial grade is used in metal polishing agents and magnetic inks, pharmaceutical grade is used as a capsule coating excipient, and electronic grade is used in the manufacture of ferrite components, applied in transformers and inductors.

- Limonite and siderite, due to their stable color and non-toxicity, are also used by artists to make oil paints and ceramic glazes.

Factors affecting Fe Ores quality and testing standards

Fe Ores Core Quality Indicators and Industry Requirements

Quality is determined by a combination of iron content, gangue content, harmful element content, and physical properties. Different application scenarios have significantly different requirements for quality indicators:

- Iron Content: Industrially, minerals with an iron content below 30% have no commercial mining value. High-grade minerals have an iron content ≥60%, and iron concentrate has an iron content ≥65%. Steel companies prefer to purchase high-grade minerals to reduce smelting costs and energy consumption.

- Gangue Content: Silicon (SiO₂) in gangue increases the consumption of slag-forming agents (lime) during smelting, reducing the blast furnace utilization coefficient. Industrial requirements ≤8% for SiO₂. Alumina (Al₂O₃) increases the slag melting point and affects slag fluidity; requirements ≤5% for Al₂O₃.

- Harmful Element Content: Phosphorus (P) causes steel to become brittle at low temperatures and easily fractures. Shipbuilding steel and steel for low-temperature equipment require P ≤0.03%, while high-end steel requires P ≤0.015%. Sulfur (S) causes steel to become brittle at high temperatures and easily cracks during high-temperature processing; requirements ≤5% for sulfur. S≤0.02%; Arsenic (As), Lead (Pb), and other elements can affect the weldability of steel, and their content must be ≤0.01%;

- Physical properties: The compressive strength of lump ore must be ≥15MPa to ensure it is not easily broken during transportation and smelting; the particle size distribution of powdered materials must meet processing requirements, with sintering powder ≥60% of -200 mesh and pelletizing iron concentrate ≥80% of -200 mesh.

Testing standards and technical methods

Testing is divided into two main categories: chemical analysis and physical property testing, using internationally recognized standards (such as ISO and ASTM) or industry standards (such as GB and JIS):

- Chemical Analysis: X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF) is used to rapidly determine the content of iron and major elements such as silicon, aluminum, and calcium, with a detection accuracy of 0.01%; atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) are used to determine the content of trace harmful elements such as phosphorus, sulfur, and arsenic; combustion infrared absorption spectrometry is used to determine the carbon and sulfur content.

- Physical Property Testing: Vibrating sieves are used to determine particle size distribution; compressive strength testing machines are used to determine the compressive strength of lump ore; and rotary drum testing machines are used to determine the mechanical strength of sintered ore and pellets. Reducibility testing is conducted by simulating the reducing environment of a blast furnace to determine the reducing power of minerals in a CO and H₂ mixed gas, assessing their smelting suitability.

- On-site Testing: During mining and trading, portable XRF analyzers are used to quickly detect ore grades, guiding mining and procurement decisions; moisture content is determined using a drying method to ensure that materials do not easily clump during transportation and storage.

Fe Ores Market and Price Trends

Supply and demand dynamics and influencing factors

- Global consumption is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 10%, with key drivers including: accelerated industrialization in emerging markets (such as India and Southeast Asia), increased infrastructure investment; expansion of global steel production capacity, with crude steel capacity projected to reach 2.3 billion tons in 2023; and increased demand for specialty steel from emerging industries (new energy vehicles, wind power, and energy storage).

- On the supply side, factors such as resource endowment, mining costs, and policy regulation are influencing demand: high-grade mineral production capacity in Australia and Brazil is steadily expanding, with Australian exports projected to grow by 2.5% to 896 million tons in 2023.

Fe Ores price fluctuations

Fe Ores prices exhibit significant cyclical characteristics, influenced by multiple factors including supply and demand, cost changes, policy adjustments, and geopolitics:

- 1900-2003: A global fixed-price mechanism resulted in long-term price stability, with the only adjustment being in 1965 from AUD 2/ton to AUD 9/ton. Industry profit margins were stable but low.

- 2003-2011: A surge in Chinese steel demand led to a sharp price increase, peaking at nearly USD 200/ton, reaching AUD 120/ton in 2011.

- 2012-2021: Global overcapacity led to a fluctuating downward price trend, with an average annual fluctuation of 30%-40%.

- 2022: Price volatility was high, peaking at USD 153.75/ton in February (driven by a recovery in Chinese demand), falling to USD 121.95/ton in June (affected by global inflation), and stabilizing at the end of the year as imports recovered.

- 2023 Monthly: Spot price was $112.37/ton (GSCI Iron Ore Index).

Future prices are expected to gradually decline, driven by key factors including: a slowdown in global blast furnace steel production growth; major steel-producing countries such as the EU, the US, and China promoting low-carbon transformation of the steel industry, leading to an increased proportion of electric arc furnace (EAF) steel (EAF steel has lower requirements for ore quality and can use scrap steel); global green development policies promoting low-emission mining and smelting technologies, reducing unit production costs; and the release of new production capacity in Australia and Brazil, resulting in ample market supply. The average price is projected to be $75/ton in 2024, decreasing to $63/ton in 2028.

As a major exporter, Australia's export revenue is projected to decrease from AUD 11.3 billion in 2022-23 to AUD 9.5 billion in 2023-24, primarily due to declining prices and fluctuations in Chinese demand.

Conclusion

Iron ore, as a core raw material for the steel industry, is determined by its geological characteristics, which shape its resource distribution pattern. Its type and attributes influence processing technology selection, its production and sales patterns are linked to global supply chain collaboration, and its processing technology determines resource utilization efficiency. These four factors together constitute the core logic of the iron ore industry, directly impacting the stable operation of the global industrial system. Hematite and magnetite, as high-grade ores, have become the mainstream types of industrial mining due to their high iron content and low impurities. Australia and Brazil, relying on their high-quality mineral resources, have established themselves as core producers and exporters, while China, based on its steel production capacity, has become a core global consumer. These three constitute the core chain of "production-trade-consumption." Surface mining, sintering, and pelletizing processes are key technologies for the industrial utilization of iron ore. Heavy machinery, as the core carrier in each stage, directly determines mining efficiency, processing quality, and overall costs based on its performance parameters and process adaptability. With the advancement of global low-carbon policies and technological upgrades, the iron ore industry will face multiple challenges, including the depletion of high-grade ore resources, rising environmental costs, and the need for scrap steel substitution. The transformation towards "efficient mining, clean processing, and resource recycling" may become a trend. The development and utilization technologies of low-grade ore, hydrogen smelting processes, and energy-saving upgrades of heavy machinery will become key areas of research and investment in the industry, promoting sustainable development.