There exists a class of metallic mineral grains in nature that, due to their striking resemblance to gold, often lead to cognitive biases in first-time discoverers. This mineral is pyrite (FeS₂), also known as iron disulfide, and colloquially as "fool's gold." As the most widely distributed sulfide mineral in the Earth's crust, pyrite's distribution spans various geological environments, and its tendency to be confused with gold has been documented extensively in the history of human mining and exploration. Pyrite is not "worthless"; it possesses unique value in mineral resource development, industrial production, traditional medicine, and collecting. The geological origins, associated mineral assemblages, and environmental impacts of pyrite have become key research areas in geological exploration, mineral processing, and environmental protection. This article will detail the geological origins, basic characteristics, identification systems with gold, historical records, diverse uses, processing techniques, and environmental impacts of pyrite, providing a comprehensive reference for understanding and practice in related fields.

What is pyrite?

Core attributes

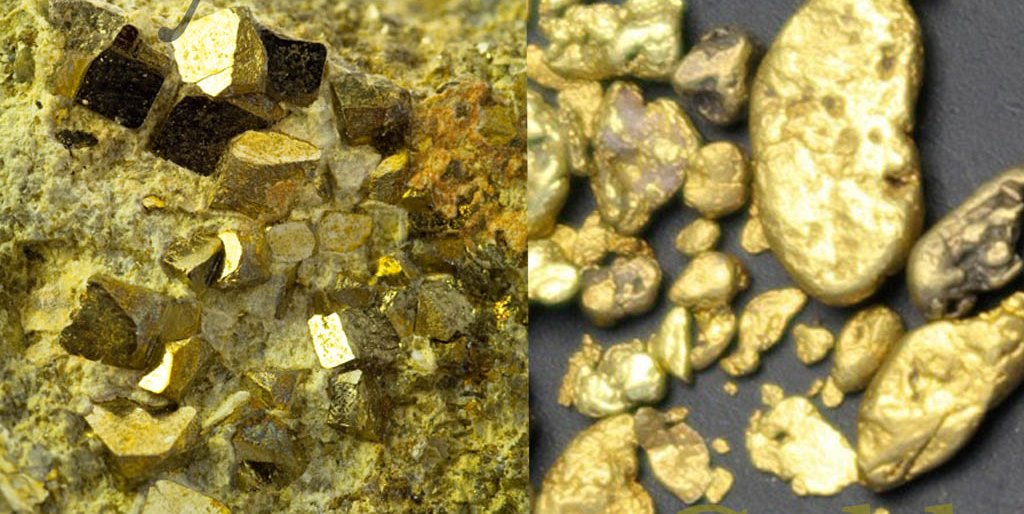

The main chemical component of pyrite is ferrous disulfide (FeS₂). Its crystal structure belongs to the isometric crystal system, with typical crystal forms being cubic and octahedral, and some exhibiting pentagonal dodecahedral forms. The crystal faces often display striations. In addition to the fixed ratio of iron to sulfur, its chemical composition often includes trace amounts of cobalt, nickel, copper, gold, selenium, and arsenic. The content and type of these associated elements are significantly influenced by the formation environment. In pure pyrite, the mass fraction of iron is 46.67%, and the mass fraction of sulfur is 53.33%. Due to its high sulfur content, it is officially named pyrite in the industrial sector, serving as a core source of sulfur resources. Among natural minerals, besides pyrite, chalcopyrite (CuFeS₂) also resembles gold in appearance. The difference lies in the fact that chalcopyrite has a more coppery-yellow color and a slightly lower hardness (3.5-4), which can be initially distinguished through hardness testing.

Origin of the name and its cultural symbolism

The name pyrite originates from the Greek word "pyr," which literally means "fire." This name stems from its unique physical properties: when minerals harder than pyrite, such as quartz and corundum, rub against its surface, the friction generates heat, causing a slight oxidation of sulfur and producing visible sparks. This property was widely used in ancient times. From the Late Neolithic to the Bronze Age, pyrite was often made into flint and steel, used in conjunction with flint to ignite fire. In early firearms (such as flintlock muskets), pyrite fragments were fixed to the hammer; the sparks produced upon impact ignited gunpowder, making it a crucial ignition material.

In cultural contexts, the symbolic meaning of pyrite is diverse across regions: ancient Egyptians ground it into powder as eyeshadow pigment, believing its metallic luster symbolized "solar energy"; ancient Greeks used it in decorative crafts, viewing it as "false gold bestowed by the earth"; in ancient Chinese texts, pyrite was called "stone marrow lead" or "natural copper," and besides its medicinal uses, it was also imbued with the folk connotation of "accumulating wealth."

Distribution characteristics and main production areas

Pyrite formation is not limited by a single geological environment and often occurs in combination with multiple rock types:

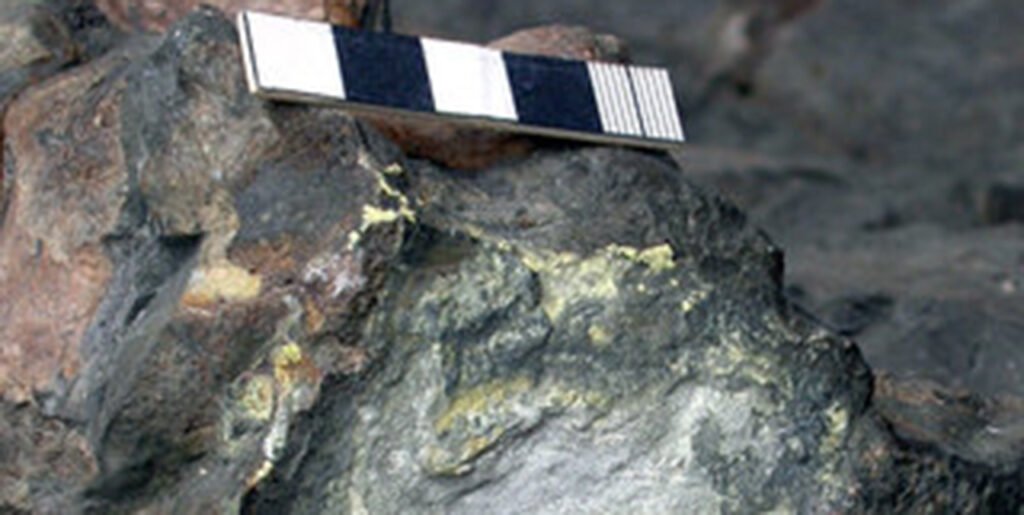

- In hydrothermal deposits formed at the contact zone between igneous rocks and surrounding rocks, pyrite is often associated with quartz, galena, and sphalerite.

- In sedimentary rocks, pyrite is commonly found in shale, sandstone, and coal seams, and is mostly a chemical sedimentary product of reducing environments during sedimentation. In metamorphic rocks, pyrite is formed by the recrystallization of sulfides in the protolith through metamorphism, and is often associated with metamorphic minerals such as garnet and mica.

The world's major pyrite producing areas exhibit a clear regional concentration:

- The Rio Tinto mine in Spain is a globally renowned large pyrite deposit, known for its large reserves and abundant associated copper and gold resources; the Příbrám mine in the Czech Republic is characterized by pyrite rich in cobalt and nickel.

- In the Nevada and California mines of the United States, pyrite is often found in association with gold, making it an important carrier of "hidden gold."

- China's pyrite resources are widely distributed, with important producing areas including Ma'anshan in Anhui, Yunfu in Guangdong, Panzhihua in Sichuan, and Datong in Shanxi. The Yunfu mine in Guangdong is China's largest pyrite production base, mainly used for sulfuric acid production and sulfur resource development.

Composition and physical properties of pyrite

The physical properties of pyrite are the core basis for its identification, mining, and application. Specific parameters and characteristics are shown in the table below:

| Category | Specific Content | Supplementary Notes |

| Chemical Formula | FeS₂ | Sulfur exists as S₂²⁻ ions, belonging to disulfides |

| Color | Pale brass-yellow | Easily oxidized when long-term exposed to the surface, forming a brownish oxide film on the surface |

| Luster | Metallic luster | Fresh fracture surfaces show strong luster; luster weakens after oxidation |

| Mohs Hardness | 6–6.5 | Can scratch glass; cannot be scratched by a pocket knife (hardness 5.5) |

| Specific Gravity | 4.95–5.10 | Slight variation depending on the content of associated elements; e.g., gold-bearing pyrite has slightly higher specific gravity |

| Tenacity | Brittle | Easily breaks along cleavage planes when struck; fracture is conchoidal or uneven |

| Crystal System | Isometric (cubic) system | Symmetry type m3̄; crystals commonly occur as cubes, octahedra, or pyritohedra |

| Common Crystal Forms | Cube, octahedron, pyritohedron (pentagonal dodecahedron) | Cube faces commonly show three sets of mutually perpendicular striations |

| Streak Color | Dark greenish-black | Streak color is stable and unaffected by surface oxidation |

| Transparency | Opaque | No light transmission regardless of crystal size |

| Associated Rock Types | Quartz veins, sedimentary rocks, metamorphic rocks, sulfides/oxides in coal seams | Grain size and dissemination characteristics of pyrite vary significantly in different host rocks |

Historical records related to pyrite

Pyrite's resemblance to gold has led to numerous cognitive biases throughout human history, with related records spanning multiple fields such as mining exploration and geographical discovery, making it a typical case in the history of mineralogy.

Records of accidental mining in ancient mining

As early as 3000 BC, during the ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, miners discovered pyrite, but due to a lack of identification techniques, it was often confused with gold. Large quantities of pyrite processed into beads have been unearthed at ancient Egyptian mining sites, suggesting it was used as "cheap gold" at the time. During the Roman era, large deposits of pyrite ore were found at mining sites in Spain. According to historical records, the Romans organized large-scale mining operations, but abandoned them because they could not extract gold. These sites serve as physical evidence of early mismining of pyrite.

Famous Cases in Geographical Exploration

In the early 17th century, British explorer Captain John Smith, leading his fleet to explore the Virginia region of North America, discovered large quantities of rocks containing golden-yellow particles along the James River. Based on the knowledge of the time, he judged that these rocks were rich in gold and shipped an entire shipload of ore to London as "the gold spoils of the New World." The Royal Society of London organized experts to conduct tests. Through specific gravity tests and high-temperature burning experiments (pyrite produces a sulfur dioxide odor when burned, while gold remains unchanged), they ultimately confirmed that the ore's main component was pyrite, and it had no practical value for gold mining. This event sparked widespread discussion in Europe, and the nickname "Fool's Gold" spread throughout the Western world.

Confusion during the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush of the 1840s and 1850s was a period of high incidence of confusion between pyrite and gold. Historical records indicate that approximately one-third of prospectors mistook pyrite for gold during this period, and between 1848 and 1850 alone, over 500 tons of "fake gold" were mined. Miners at the time lacked scientific identification methods, relying mainly on visual inspection and simple tapping, leading to a significant waste of manpower and resources. To address this problem, some mining areas began employing mineralogists to promote methods such as streak testing and specific gravity testing, gradually reducing the misidentification rate. These confusions during this period also spurred the popularization of mineral identification techniques among the general public.

Historical Evolution of Identification Technology

Before the 19th century, the identification of pyrite and gold mainly relied on empirical methods, such as "feeling weight" and "sound when tapped" (gold produces a dull sound when tapped, while pyrite produces a crisper sound). In the mid-19th century, after the invention of the Mohs hardness tester, hardness testing became an important identification method. In the early 20th century, the application of chemical analysis and X-ray diffraction technology enabled the accurate determination of the composition and crystal structure of pyrite. In modern mining, portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometers (XRF) can quickly detect the gold content and elemental composition in ores on-site, fundamentally solving the problem of identifying pyrite and gold.

Methods for distinguishing pyrite from gold

Pyrite and gold differ fundamentally in their physical and chemical properties, and can be accurately distinguished through a multi-dimensional, step-by-step identification system. The specific methods are as follows:

Identification by appearance and feel (basic identification)

- Color and Luster: Gold is golden yellow or reddish yellow with a soft, malleable luster (the luster remains unchanged after rubbing); pyrite is light brassy yellow with a strong metallic luster, and its surface easily oxidizes, forming brownish spots, resulting in uneven luster.

- Specific Gravity Difference: For the same volume, gold's specific gravity (19.3) is approximately four times that of pyrite (4.95-5.10), resulting in a significant difference in feel. In practice, the "displacement method" can be used: take equal volumes of ore samples and weigh them separately. The one with a weight close to 19.3 g/cm³ is gold, and the one closer to 5 g/cm³ is pyrite. A simpler method is to feel the weight in your hand; gold feels heavy, while pyrite is relatively light.

Physical property identification (intermediate level)

- Hardness Test: Use a Mohs hardness tester or a common hard object for testing. Gold has a Mohs hardness of 3 and can be scratched by a knife (hardness 5.5) or a copper coin (hardness 3.5), with the scratch color matching the gold itself. Pyrite has a Mohs hardness of 6-6.5 and can scratch glass (hardness 5.5), but cannot be scratched by a knife. If forcefully scratched with a knife, only a white scratch (not a metallic scratch) will be left.

- Stroke Test: Take a white unglazed porcelain plate and gently scratch the ore sample on it, observing the color of the scratch. Gold's streak is golden yellow, matching the color of the ore itself, and the streak is fine and lustrous. Pyrite's streak is dark green, contrasting sharply with the light brass color of the surface, and the streak lacks metallic luster. This method is unaffected by surface oxidation and is one of the most stable identification methods.

- Toughness Test: Hold the ore sample with tweezers and gently tap it. Gold is malleable and will deform when impacted, but will not break; pyrite is brittle and will break along cleavage planes when impacted, producing irregular fragments with a conchoidal fracture surface.

Chemical and instrumental identification (precise identification)

- Chemical Testing: Take a small amount of ore powder and add dilute nitric acid (concentration 10%-15%). Gold does not react with dilute nitric acid, and the powder remains unchanged; pyrite reacts violently with dilute nitric acid, producing a yellow precipitate (sulfur) and a reddish-brown gas (nitrogen dioxide), and the solution turns yellow (iron ions). Note: This method will damage the ore sample and is only suitable for non-collectible ores.

- Instrumental Testing: A portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF) can quickly detect the elemental composition and content in the ore. Gold samples will show a high content of Au, while pyrite samples are mainly composed of Fe and S, with very low levels of associated elements; X-ray diffraction (XRD) can accurately determine the type of ore through crystal structure analysis. Gold is a metallic crystal, while pyrite is an isometric sulfide crystal, and the diffraction peaks show significant differences.

The value and uses of pyrite

The value of pyrite is not limited to being a "common gold" mineral; its uses cover multiple fields such as industrial production, traditional medicine, and ornamental collection, making it a multifunctional mineral resource.

Mineral resource value: Extraction of gold and associated elements

Pyrite and gold form under similar conditions (both in low-to-medium temperature hydrothermal environments), and their symbiotic relationship is close. In some hydrothermal deposits, gold in pyrite exists as "hidden gold"—gold particles smaller than 0.1 micrometers, uniformly encapsulated within pyrite crystals or adsorbed on the crystal surface, with a content of 0.25%-1%. This type of pyrite-bearing pyrite is an important supplementary source of commercial gold, with approximately 15%-20% of global gold production coming from the comprehensive recovery of pyrite.

Regarding extraction processes, a combined "flotation-cyanide leaching" process is commonly used for pyrite-bearing pyrite: first, pyrite is enriched into a concentrate through flotation; then, gold is leached using sodium cyanide solution; finally, gold mud is obtained through zinc powder replacement, and pure gold is obtained through smelting. Associated elements (cobalt, nickel, copper, selenium) in pyrite also have recycling value. For example, the cobalt content in pyrite concentrate from the Rio Tinto mine in Spain can reach 0.05%-0.1%. Cobalt can be recovered through a combination of magnetic separation and flotation processes and used in the production of lithium battery materials.

Core industrial applications: sulfur resource and chemical product production

Pyrite is the world's most important source of sulfur, with approximately 70% of global sulfuric acid production using it as a raw material. The specific process is as follows:

- Roasting: Pyrite concentrate is roasted at high temperature (850-950℃) in a fluidized bed furnace, reacting to generate sulfur dioxide (FeS₂ + O₂ → Fe₂O₃ + SO₂);

- Purification: The sulfur dioxide-containing flue gas generated during roasting is treated with dust removal, desulfurization, and drying to remove impurities;

- Conversion: Under the action of a catalyst (vanadium pentoxide), sulfur dioxide is oxidized to sulfur trioxide (SO₂ + O₂ → SO₃);

- Absorption: Sulfur trioxide is absorbed with 98.3% concentrated sulfuric acid to generate industrial-grade concentrated sulfuric acid.

Besides sulfuric acid production, the sulfur dioxide produced from pyrite roasting can be used in the bleaching process of the paper industry, replacing traditional chlorine bleaching and reducing environmental pollution. The waste residue after roasting (mainly iron oxide) can be used to produce iron oxide red pigment or as a cement additive. Pyrite is used as a colorant in glass manufacturing; when added at a ratio of 0.5%-1.5%, it can give the glass a uniform amber color, which is used to make specialty glasses such as cosmetic bottles and beverage bottles.

Ornamental and collectible value

Pyrite crystals, due to their regular shape and strong luster, possess extremely high ornamental and collectible value. Among them, cubic pyrite crystals (side length 2-5 cm) and cubic and octahedral aggregate crystals are popular varieties in the collector's market. High-quality specimens can fetch 5-20 yuan per gram, while large, complete crystals (side length over 10 cm) can exceed 10,000 yuan.

Globally renowned pyrite crystal deposits include Illinois in the United States, Junín Province in Peru, and Chenzhou in Hunan Province, China. Pyrite crystals from these regions are known for their smooth crystal faces, clear striations, and lack of breakage. Some high-quality crystals, after cutting and polishing, can be used as low-grade gemstones to make pendants, earrings, and other jewelry; their metallic luster and unique color are highly sought after by niche collectors. Pyrite crystals often occur in association with minerals such as quartz and calcite, forming composite specimens that are important exhibits in geological museums and university geological laboratories.

Medicinal value

Pyrite, after being processed through calcination and vinegar quenching, is called "natural copper," a commonly used mineral medicine in traditional Chinese medicine. It was first recorded in the Shennong Bencao Jing (Shennong's Classic of Materia Medica) and listed as a medium-grade medicine. Modern pharmaceutical research shows that the main component of calcined natural copper is iron oxide (Fe₂O₃), with trace amounts of copper, cobalt, and other elements. Its medicinal effects include promoting blood circulation, removing blood stasis, and healing bones and tendons, and it is commonly used to treat injuries, fractures, and swelling caused by blood stasis.

In clinical applications, natural copper is often used in combination with other traditional Chinese medicines such as angelica, safflower, and frankincense to prepare decoctions, powders, or external plasters. Modern pharmacological experiments show that the iron in natural copper can participate in the synthesis of hemoglobin in the human body and promote calcium deposition during bone healing. Its blood-activating and stasis-removing effects may be related to improving local blood circulation. Caution: Natural copper is warm in nature; those with yin deficiency and excessive internal heat should use it with caution and under the guidance of a professional physician to avoid excessive dosage.

The relationship between pyrite and iron extraction

Although pyrite contains iron (46.67% iron in pure pyrite), it has never been used as a major raw material for iron smelting in industry. The main reasons are as follows:

Iron content and extraction efficiency

Pyrite has a lower iron content than high-quality iron ore: the theoretical iron content of hematite (Fe₂O₃) is 70%, magnetite (Fe₃O₄) is 72.4%, while pyrite is only 46.67%. Furthermore, in actual deposits, the iron content of pyrite often drops below 40% due to associated impurities. The iron in pyrite is tightly bound to sulfur, requiring roasting to remove sulfur before iron can be extracted. This process is complex, energy-intensive, and the extraction cost is 2-3 times that of smelting iron from hematite, making it economically infeasible.

Environmental pollution

The iron smelting process from pyrite generates a large amount of sulfur dioxide gas: approximately 0.8 tons of sulfur dioxide are produced for every ton of pyrite processed. Direct emissions would cause serious environmental problems such as acid rain and air pollution. Although desulfurization equipment can be used to treat this, it would further increase investment and operating costs. In contrast, the iron smelting process from iron oxide ores such as hematite and magnetite only produces carbon dioxide and a small amount of dust, making pollution control easier and less costly, and thus meeting environmental protection requirements.

Raw material selection for industrial ironmaking

Hematite and magnetite are the core raw materials for global industrial ironmaking, accounting for over 95% of the total raw materials used in ironmaking. In China, hematite is the primary raw material for ironmaking (60%), followed by magnetite (30%), mainly sourced from large iron ore deposits such as Qian'an in Hebei, Bayan Obo in Inner Mongolia, and Anshan in Liaoning. These ores have advantages such as high iron content, low impurities, and low mining costs, making them the optimal choice for the ironmaking industry.

Pyrite processing technology

The processing technology of pyrite depends mainly on its use and dissemination characteristics. The core objective is to enrich and purify pyrite. Commonly used processes include gravity separation, flotation and combined processes.

Gravity separation process (for coarse-grained ore processing)

Gravity separation utilizes the difference in specific gravity between pyrite and gangue to achieve separation. It is suitable for ores with relatively coarse-grained particles (greater than 0.074 mm) and is the main process for pyrite processing, offering advantages such as low cost, low energy consumption, and no pollution.

Common equipment and working principles:

- Separation of Ores: Jig: The heavier pyrite particles settle rapidly along the inner side of the trough, while the lighter gangue (quartz, feldspar, etc.) moves along the outer side, resulting in separation. This equipment is suitable for processing ores with a particle size of 0.074-2 mm, achieving a recovery rate of 85%-90%.

- Jig: The periodic pulsation of water flow causes the pyrite particles to move up and down in the jigging chamber. Pyrite particles, due to their greater weight, settle quickly and concentrate at the bottom of the jigging chamber as concentrate; gangue particles settle slowly and are discharged with the water flow as tailings. This is suitable for processing ores with a particle size of 0.5-10 mm, and is particularly suitable for enriching coarse-grained pyrite.

- Shaking Table: Utilizing the reciprocating motion of the table surface and the washing effect of the transverse water flow, the pyrite particles are stratified according to their specific gravity. Pyrite is enriched at the concentrate end of the table surface, while gangue is discharged from the tailings end. This equipment has high separation accuracy and is suitable for processing ores with a particle size of 0.02-2 mm. It can be used for secondary purification of pyrite concentrate.

Typical process: Raw ore → Crushing (jaw crusher) → Grinding (ball mill) → Classification (spiral classifier) → Gravity separation (spiral chute / jig / shaking table) → Dewatering (thickener + filter) → Pyrite concentrate (sulfur content ≥35%).

Flotation process (fine-grained ore processing)

Flotation utilizes the differences in surface physicochemical properties between pyrite and gangue, achieving separation by adding flotation reagents. It is suitable for ores with finely distributed (less than 0.074 mm) or unevenly distributed particles.

Flotation reagent system:

- Collectors: Commonly used xanthates (such as butyl xanthate) and black oxides selectively adsorb onto the surface of pyrite, making it hydrophobic;

- Frothing agents: Commonly used pine oil and MIBC, which generate stable foam, allowing hydrophobic pyrite particles to adhere to the foam surface;

- Modifiers: Commonly used lime and sulfuric acid, used to adjust the pH of the slurry and inhibit the floatability of gangue minerals.

Typical process: Raw ore → Crushing → Vertical roller mill Grinding → Classification → Slurry preparation (addition of reagents) → Flotation (flotation machine) → Froth concentrate → Dewatering → Pyrite concentrate (sulfur content ≥38%)

Gravity separation-flotation combined process (processing of uneven particle size ore)

For ores with uneven particle size distribution (coexistence of coarse and fine particles), a single process cannot achieve efficient recovery; a combined gravity separation-flotation process is required. The specific process is as follows:

- After pyrite crushing and grinding using VRM, the raw ore is first classified by a spiral classifier into coarse-grained (greater than 0.074 mm) and fine-grained (less than 0.074 mm) particles.

- The coarse-grained ore is processed using gravity separation (jigging + shaking table) to obtain coarse-grained concentrate.

- The fine-grained ore is processed using flotation to obtain fine-grained concentrate.

- The two concentrates are combined, dehydrated, and dried to obtain the final pyrite concentrate, with a total recovery rate of 90%-95%.

Specialized processing technology for pyrite

The processing of pyrite-bearing ore focuses on gold recovery and commonly employs a process of "flotation enrichment - cyanide leaching - zinc powder replacement".

- Flotation enrichment: Pyrite is enriched into concentrate through flotation, improving the gold grade;

- Roasting pretreatment: Pyrite concentrate is roasted at 600-700℃ to destroy the pyrite crystal structure, exposing the "hidden gold";

- Cyanide leaching: Roasted ore is added to a sodium cyanide solution (concentration 0.05%-0.2%), where gold forms a complex with cyanide and dissolves in the solution;

- Zinc powder replacement: Zinc powder is added to the cyanide solution to replace the gold, forming gold mud;

- Smelting and purification: After drying and roasting, the gold mud is smelted using pyrometallurgy (1200-1300℃) to obtain pure gold (purity ≥99.9%).

Environmental impact and remediation of pyrite

The mining and processing of pyrite may cause environmental problems, mainly including acid mine drainage and heavy metal pollution, which need to be addressed through scientific measures.

Major environmental issues

- Acidic Mine Wastewater (AMD): When pyrite is exposed to air, it undergoes oxidation in the presence of water, oxygen, and microorganisms (such as Thiobacillus ferrooxidans), producing sulfuric acid and ferrous sulfate. This causes the pH of the mine wastewater to drop to 2-4, forming acidic wastewater. Acidic wastewater corrodes equipment, pollutes soil and groundwater, and dissolves heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, and mercury from the ore, causing secondary pollution.

- Solid Waste Pollution: Tailings from pyrite mining still contain a certain amount of pyrite. If improperly disposed of, they will continue to oxidize and produce acidic wastewater. Roasting slag, if not properly treated, may lead to heavy metal leaching pollution.

Governance measures

- Acidic wastewater treatment: A "neutralization precipitation-filtration" process is used. Neutralizing agents such as lime or limestone are added to the acidic wastewater to adjust the pH to 6-9, causing iron and heavy metal ions to form hydroxide precipitates. The precipitates are then removed by filtration, and the treated wastewater meets discharge standards or can be recycled.

- Tailings treatment: Tailings are coated with a membrane to reduce oxygen-water contact and inhibit pyrite oxidation; or acid-tolerant plants (such as ryegrass and foxtail grass) are planted on the surface of the tailings pile to absorb heavy metals through their roots, improving the soil environment.

- Clean production technology: Low-pollution processing technologies are promoted, such as using dry beneficiation instead of wet beneficiation to reduce wastewater generation; circulating fluidized bed boilers are used in the roasting process to improve sulfur recovery and reduce sulfur dioxide emissions.

Conclusion

Pyrite, the most widely distributed sulfide mineral in the Earth's crust, is commonly known as "fool's gold" due to its resemblance to gold. The two can be accurately identified through physical properties such as specific gravity, hardness, and streak, as well as chemical and instrumental testing. Although pyrite is not gold, it possesses multiple values: as a carrier of "hidden gold," it is an important supplementary source of commercial gold; as a core sulfur resource, it supports the development of the global sulfuric acid and chemical industries; and it also has functions such as ornamental collection and traditional medicinal uses. In terms of processing technology, gravity separation is the main method for processing coarse-grained pyrite, flotation is suitable for fine-grained ores, and combined processes can handle complex ores with uneven distribution. The application of various processes must be comprehensively selected based on the characteristics of the ore and its intended use. Environmental problems such as acidic mine drainage and heavy metal pollution generated during pyrite mining and processing need to be effectively addressed through neutralization treatment, tailings coating, and clean production technologies. Research and application of pyrite will focus on three directions: first, the comprehensive recovery of mineral resources, improving the recovery rate of associated elements such as gold, cobalt, and nickel; second, the development of environmentally friendly processing technologies to reduce energy consumption and pollutant emissions; and third, the exploration of new application areas, such as utilizing pyrite's semiconductor properties (bandgap of 0.95 eV) to develop photovoltaic materials and catalysts. These characteristics and potential value of pyrite will ensure its continued important position in geological research, mineral development, industrial production, and environmental protection.